Richard Jerram

Chief Economist, Bank of Singapore

Member of OCBC Wealth Panel

On 23 June this year, the UK electorate surprised the world by voting to leave the European Union (EU). Many weeks later, the timeline and process towards exit remains fuzzy and this will likely weigh on the economy in the medium-term.

Expect material slowdown in growth

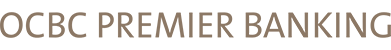

The short-run economic outlook is not great. The UK has and will continue to experience a material slowdown in growth due to the Brexit vote. As it is, the UK economy was already showing signs of softness due to uncertainty ahead of the referendum and this will only intensify over the coming year. Notably, the UK’s services and manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) drastically deteriorated in July, signalling weak business confidence after the vote.

Bank of England to the rescue

The Bank of England (BOE) has delivered a broad monetary stimulus package including a 25 basis points rate cut and an expansion of their quantitative easing programme. This should provide some near-term support for the economy.

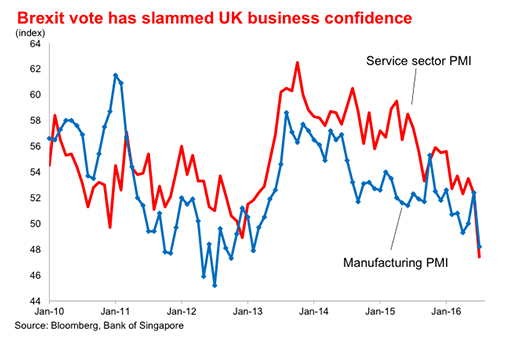

Meanwhile, the badly battered GBP should reduce the hit on the economy. A lower exchange rate stimulates exports and supports import-competing sectors, which should help mitigate the some of the adverse near-term impact on growth. We’ve seen this happen before in 1992 during the Black Wednesday episode. Back then, the plunge in the Pound quickly yanked the economy out of the recession. As several commodity exporters have discovered in the past couple of years, the exchange rate is a wonderful shock absorber.

Economic impact of Brexit contained

The global impact of a UK slowdown should be muted at best considering that that the UK accounts for a small 2.3 per cent of global GDP.

The impact to the European economy might be more material considering its deep trade linkages. While some of the investment flows and financial sector activity will migrate to the EU, the region is likely to see short-term damage from the uncertainty and the hit to trade flows with the UK. Moreover, the UK’s improved competitiveness after the plunge in GBP is the Eurozone’s loss, which will slow growth.

However, the damage seems manageable considering that the period of European austerity is over and Eurozone growth has been comfortably above trend for the past couple of years, as shown by the steady drop in the unemployment rate. Also, Eurozone businesses seem to have shrugged off Brexit risks as seen in recent PMI data, which has been stable at elevated levels.

Moreover, we can expect the European Central Bank to extend and expand its quantitative easing programme in order to limit downside risks. There should not be too many concerns about financial system stability following the tighter regulatory stance and increase in capital buffers seen in recent years.

Limited damage to the London property scene

Declining prices in the London property market on the back of weak consumer confidence has attracted investor attention looking for property bargains. The property market also looks cheap because of the weak Pound, but it is important to note that rental has also gone lower so yields on investing in London property are not attractive.

The damage to the property market should be fairly limited as well given the recent monetary easing by the BOE which has lowered borrowing costs. In addition, Brexit is unlikely to dim London’s appeal as a global city and there will always be buyers who are willing to invest in property even at higher prices. This means London property is never going to be particularly cheap. The stock market should be more of a bargain for investors relative to property.

As the economic effects of Brexit continue to unfold in the next few months, we expect the Pound to trend even lower, heading closer to 1.70 and below against the SGD by the end of the year. At these levels, London property might be more attractive.

Broader implications

The long-term implications of Brexit are uncertain as exit terms are far from final. If the UK loses free access to the EU market, there’s no doubt that they would be worse off from an economic standpoint. After all, one thing most economists agree on is the unambiguous benefits of free trade.

Immigration reform can also affect the economy adversely in the long term if it means curbing the inflow of higher-skilled workers.

It also remains uncertain as to how far the British government can ease business and financial regulations beyond EU-standards before provoking backlash from other member countries.

Beyond the economic, the existential threat to the project of European integration is probably the biggest risk from Brexit. Other countries will face pressure to follow the UK vote, although exit would be much more complicated for those that are members of the Eurozone. Exit from the monetary union will be far more disruptive than Brexit. The response might not be immediate, but if the UK fares well outside the EU then others might be tempted to follow.

Elections in France, the Netherlands and Germany in 2017 will be a focus for market concern, especially as the UK has illustrated the unpredictability of events and the poor reliability of opinion polls.

On a more positive note, Brexit should send a strong message to EU institutions that might help to drive reform, but this is likely to be slow-moving compared to the rise in nationalist sentiment among some EU members.

The failure of polls

The failure of opinion polls or prediction (betting) markets to foresee the result is worth mentioning as well. With polls seemingly unreliable, markets will likely see greater unpredictability around future political events. This is especially relevant to the approaching U.S. presidential election, where it might be difficult to have a reliable guide to the chance of Donald Trump winning.

It seems that there is a “Bradley effect” at work. This is where voters are reluctant to reveal their true preferences to pollsters. Originally this was based on the public’s reluctance to admit that they would not vote for an African-American candidate (Tom Bradley) as California’s governor in 1982. Similarly people were perhaps ashamed to admit that they favoured Brexit, in case they were seen as racist or nationalist. We might have the same problem in assessing the chances of Trump.

Important Information

The information provided herein is intended for general circulation and/or discussion purposes only. It does not take into account the specific investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of any particular person. The information in this document is not intended to constitute research analysis or recommendation and should not be treated as such.

Without prejudice to the generality of the foregoing, please seek advice from a financial adviser regarding the suitability of any investment product taking into account your specific investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs before you make a commitment to purchase the investment product. In the event that you choose not to seek advice from a financial adviser, you should consider whether the product in question is suitable for you. This does not constitute an offer or solicitation to buy or sell or subscribe for any security or financial instrument or to enter into a transaction or to participate in any particular trading or investment strategy.

The information provided herein may contain projections or other forward looking statement regarding future events or future performance of countries, assets, markets or companies. Actual events or results may differ materially. Past performance figures are not necessarily indicative of future or likely performance. Any reference to any specific company, financial product or asset class in whatever way is used for illustrative purposes only and does not constitute a recommendation on the same.

Foreign currency investments or deposits are subject to inherent exchange rate fluctuations that may provide opportunities and risks. Earnings on foreign currency investments or deposits would be dependent on the exchanges rates prevalent at the time of their maturity if any conversion takes place. Exchange controls may be applicable from time to time to certain foreign currencies. You should therefore determine whether any foreign currency investment is suitable for you in the light of your investment objectives, financial means and risk profile. Any pre-termination costs will be deducted from your deposit.

OCBC Bank, OCBC Investment Research Private Limited, OCBC Securities Private Limited, Bank of Singapore and their respective associated and connected corporations together with their respective directors and officers may have or take positions in any securities mentioned in this report and may also perform or seek to perform broking and other investment or securities related services for the corporations whose securities are mentioned in this report as well as other parties generally.

No representation or warranty whatsoever (including without limitation any representation or warranty as to accuracy, usefulness, adequacy, timeliness or completeness) in respect of any information (including without limitation any statement, figures, opinion, view or estimate) provided herein is given by OCBC Bank and it should not be relied upon as such. OCBC Bank does not undertake an obligation to update the information or to correct any inaccuracy that may become apparent at a later time. All information presented is subject to change without notice. OCBC Bank shall not be responsible or liable for any loss or damage whatsoever arising directly or indirectly howsoever in connection with or as a result of any person acting on any information provided herein.

The contents hereof may not be reproduced or disseminated in whole or in part without OCBC Bank's written consent.

© Copyright 2016 - OCBC Bank | All Rights Reserved. Co. Reg. No.: 193200032W