Mail-in chaos?

On the Tuesday after the first Monday in November

Many might not remember the exact date, but they would roughly recall that sometime in early November four years ago, their phones were probably abuzz with news alerts about the guy from “The Apprentice” winning the US presidential elections. Many were shocked, not least because Hillary Clinton was ahead in the polls and, if anything, she certainly seemed the most qualified for the role. It was a clean sweep for the Republicans then, as they took control of the House of Representatives, the Senate and the White House. With the same party controlling both the legislative and executive branches of government, President Donald Trump had immense latitude to pass his agenda.

Looking back, the 2016 election was a fairly quick and standard affair and the outcome was conclusive. The 2016 elections were held on Tuesday, 8 November (all US presidential elections are held on “the Tuesday next after the first Monday in the month of November of the year in which they are appointed”) and the results were known by the next day. It was a decisive victory for Trump, who won 304 electoral college votes, 34 more than he needed to win the presidential contest, although Hillary Clinton won the popular vote. The point is uncertainty about the outcome of the elections was lifted fairly quickly, over the span of a day, and the focus of the market moved away from the election outcome to something else over the next few trading sessions.

This time, it might be different. In the event of a close race, we might not know the winner of the elections until days or weeks later. This is largely the result of the way the elections are conducted this year.

The predicament of mail-in voting

Americans are exercising their right to vote under rather unusual circumstances, not least among them being a pandemic. Elections are dangerous affairs during a pandemic as it often entails long lines at the polls and a mass congregation of people.

Typically, voters in the US can cast their votes in one of three ways, namely:

- in-person voting during election day,

- in-person voting before election day or

- voting by mail or absentee ballots.

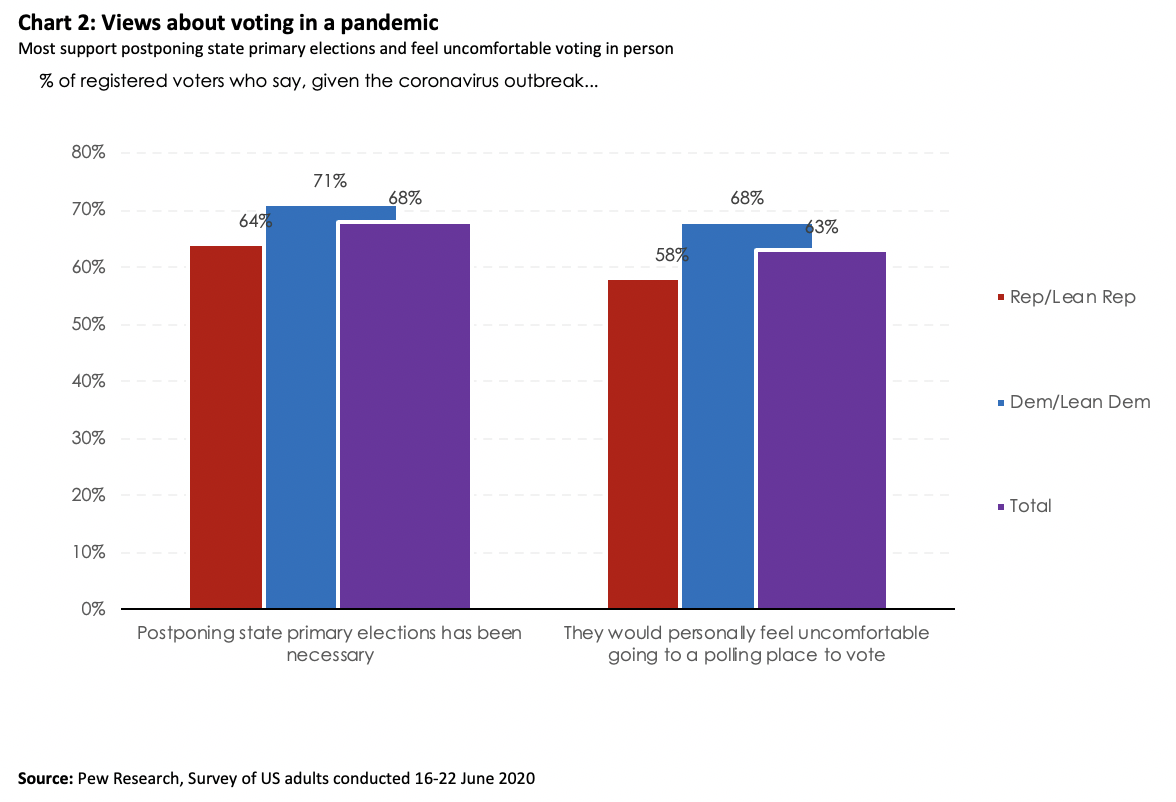

Due to social distancing restrictions and safety considerations during this pandemic, voting by mail or absentee ballots is the safest mode of casting one’s vote as it dramatically limits the need to congregate at polling stations. To be clear, there is no legal distinction between mail-in and absentee ballots. In fact, many states consider them the same thing. Either way, voters opting for these modes will not appear in person at a polling station to vote. For the purposes of this report, we use these terms interchangeably.

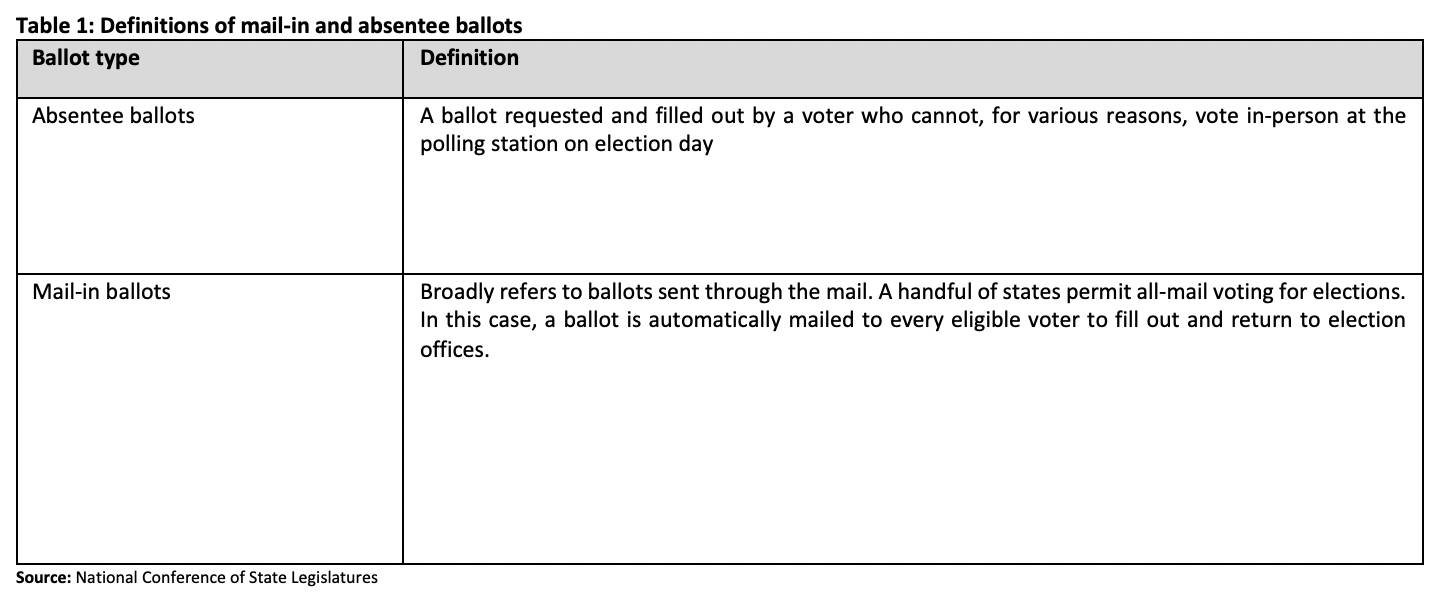

Looking at past voting trends, there has been a steady uptick in the share of voters voting by mail or absentee ballot. This is expected to rise sharply in the current election cycle as long as the pandemic remains a threat to public health.

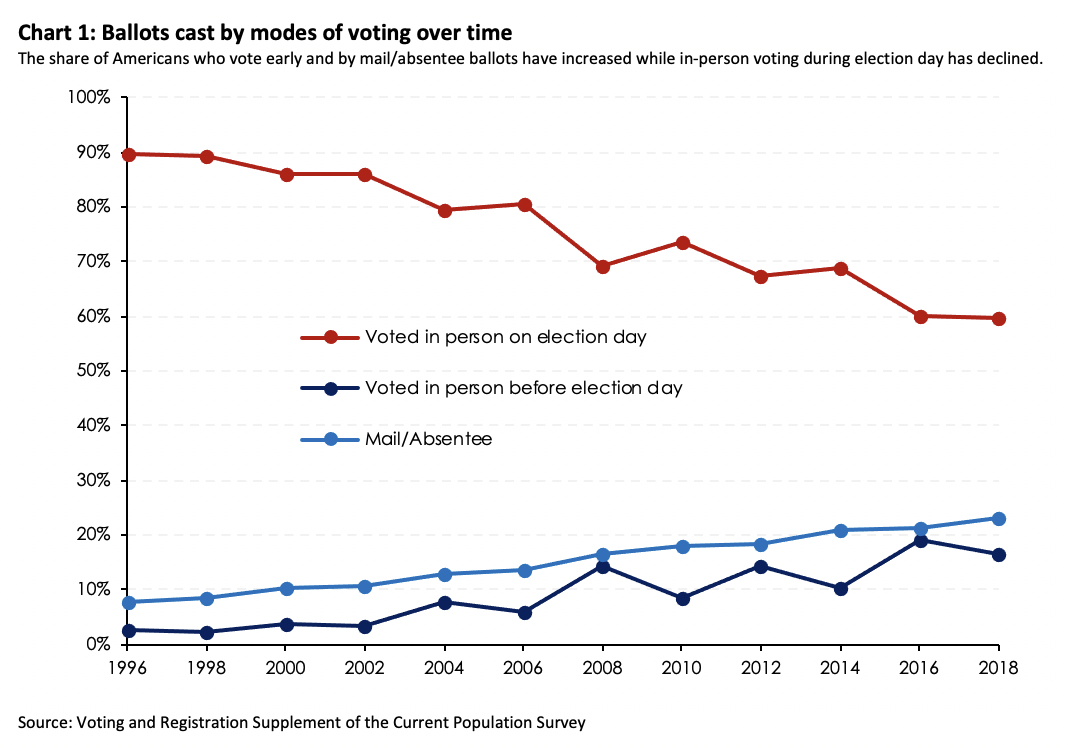

Based on calculations by the New York Times, more than 75% of American voters will be eligible to receive a ballot in the mail for the 2020 elections. Meanwhile, in a recent Pew Research survey, a majority of respondents noted that they are “uncomfortable” heading to traditional polling stations to vote on election day.

A logical alternative would be to vote by mail or to vote in-person before election day. Given the rising popularity of absentee or mail-in voting, we could expect the share of voters using these methods to cast their ballots to increase sharply this year.

Different strokes for different states

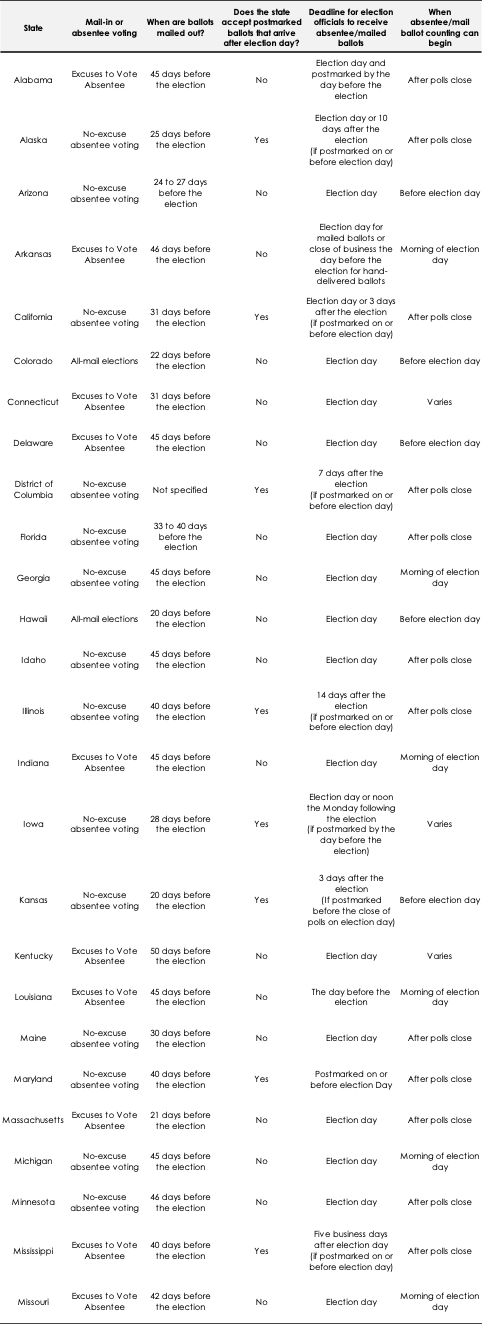

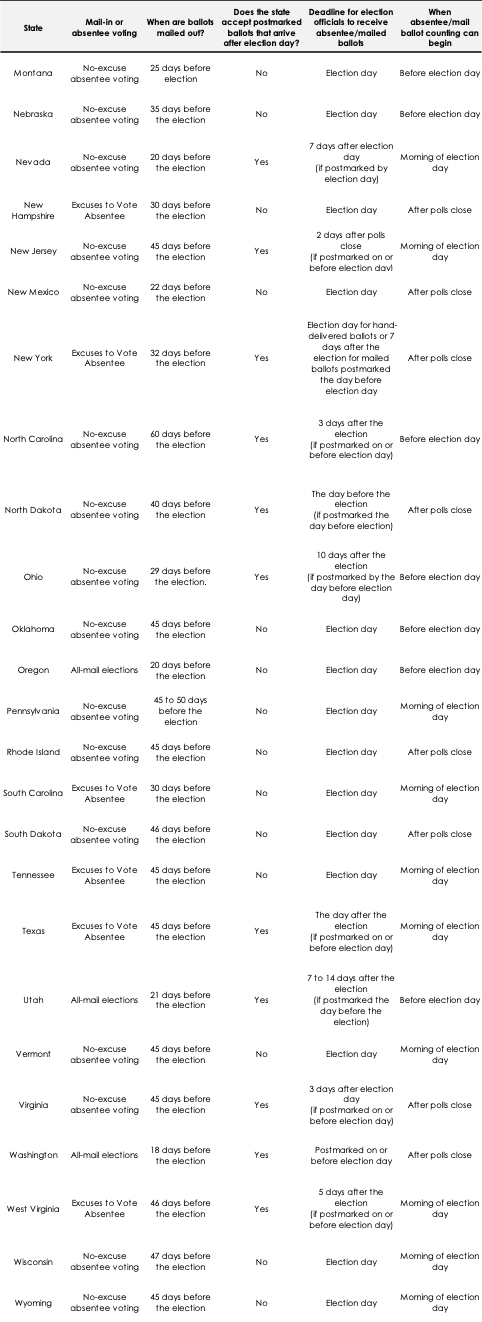

In the US, individual states are given wide latitude to administer and conduct federal elections. As a result, the way elections are run can differ markedly between states. Appendix A provides a summarised view of how 51 different states approach voting by mail or absentee ballots. We make some important observations based on the table and their potential implications on the upcoming election.

First, voting by mail or absentee ballot is not at all uncommon in the US. In fact, voting by mail is standard practice in five states. In another 30 states, voters can request for absentee ballots without having to specify a reason. In 16 other states, voters need to provide an excuse for why they are unable to vote in person when requesting for an absentee ballot. Given the pandemic, it is unsurprising that many states are reviewing their voting options and are looking to make it easier – not harder – to vote by mail or in absentia.

While this mode of voting is not new, the volume of mailed ballots that will have to be processed, verified and tallied this November probably is. Save for the five states that have been conducting elections entirely by mail for years, states with comparatively less experience in managing mail-in voting may face an unprecedented flood of mailed ballots that they may not be well-equipped to handle. According to The New York Times, experts expect roughly 80 million mailed ballots to flood election offices this November, more than double the number that was returned in 2016.

Second, ballots will be mailed to voters as early as six weeks before the November elections. If ballots cast by mail is the main mode of voting this election cycle, it is possible that a majority of the electorate will be casting their ballots – hence determining the outcome of the election – weeks or days before the election itself. This gives weight to the predictive power of polling data in the weeks leading up to the election rather than a final reading of the polls in the morning of election day itself.

The third observation relates to the receipts of these ballots. Some states require absentee or mailed ballots to reach election offices by election day. Others will still accept mailed ballots several days after the election as long as the ballots are postmarked on or before the election date. Importantly, ballots cast after election day is NOT considered constitutionally valid. As a result, most states require ballots to be postmarked before or on election day to certify that these ballots were cast in time, especially if they reached election offices days after the election.

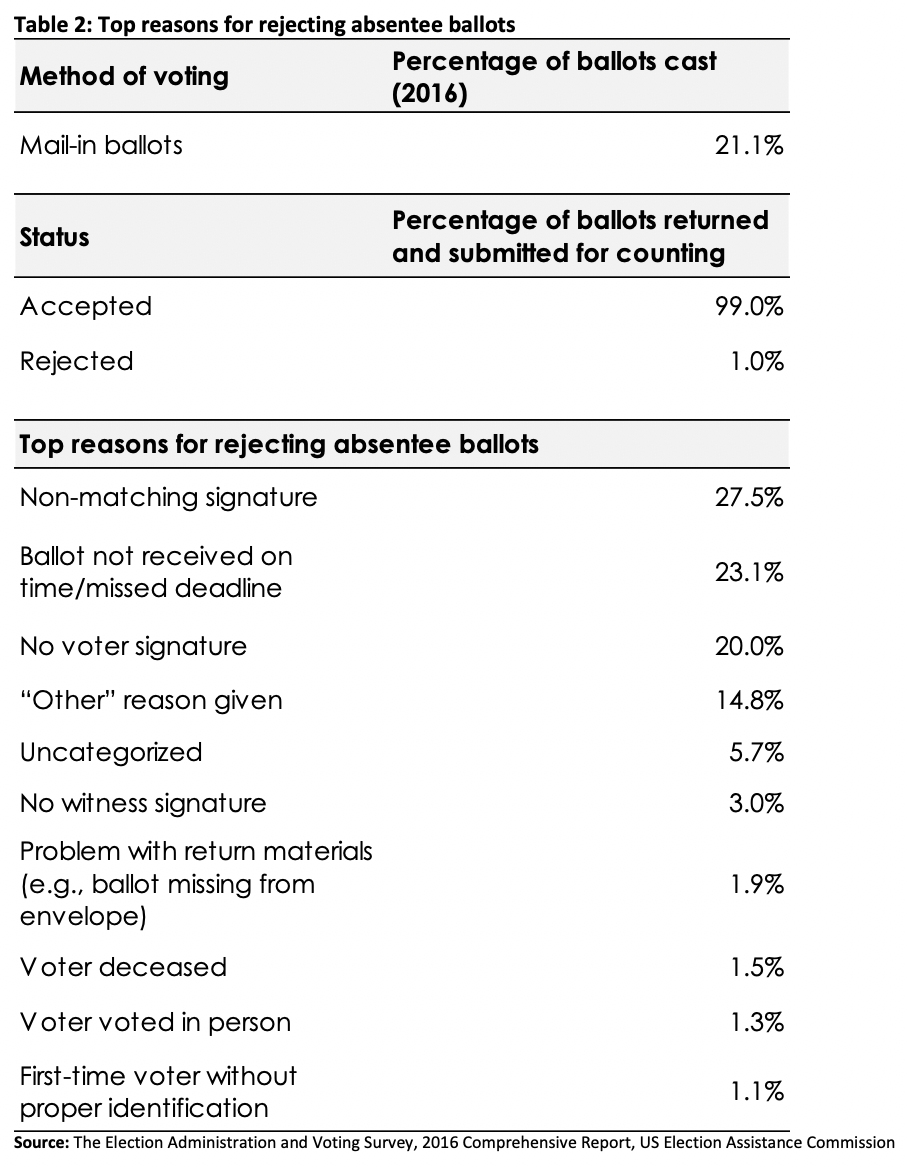

Also, mailed ballots must be processed and verified, and for most states this happens before election day, as and when they receive these ballots. Typically, mailed ballots are tallied on the morning of or after polls are closed on election day. Essentially, it takes time to process and tally mailed ballots. Table 2 gives a snapshot of the common reasons for the rejection of mailed votes during the 2016 presidential election.

Given the time taken to process mailed ballots, in addition to the fact that mailed ballots tend to come in waves and that many jurisdictions still accept ballots after polls are closed as long as they are postmarked by election day, the final results of the election might not be announced on election night itself. Indeed, the flood of mailed votes may trigger long delays in tabulating the results.

This is not at all a far-fetched notion. In fact, the results of numerous primary races in states like New York, Pennsylvania, Georgia and others were announced weeks after the various elections were held, primarily because polling centres struggled to process and tally a huge influx of mail-in and absentee ballots as voters shunned in-person voting in record numbers. The volume of mailed ballots returned in New York City for the 23 June primary elections was ten times higher than usual. In Pennsylvania, 1.5 million people cast their votes for the primary through absentee or mail-in ballots, 17 times the number that voted in absentia during the 2016 primaries. And these are just for intra-party primary races to select the Democratic and Republican nominees who will contest in November. Inter-party races for the Senate, the House of Representatives and the White House will be far larger in scale and scope.

Delays are just one aspect of the problem. You could also expect confusion emerging in a situation where tallies of in-person votes and mailed ballots returned before election day show one candidate in the lead, but a tally of uncounted mailed ballots received late or in subsequent days after the election alters the initial results. In more concrete terms, initial counts may put President Trump in the lead on the night of the election when television networks typically call the winner of the race but mailed ballots tallied in subsequent days could as easily alter the results in Biden’s favour. Indeed, conditions are ripe for such late swings to happen across many states due to the potentially unprecedented increase in mail-in voting during this election cycle.

These problems become ever more acute for very tight races in battleground states such that it may trigger a series of legal challenges for votes to be recounted if the margin of defeat is very slim. We have seen this movie before in 2000 during the contentious Bush versus Gore election.

Then Texas Governor George W Bush lost the national popular vote to Vice President Al Gore, and was neck and neck in terms of the electoral college, which ultimately determines the winner of the election. It came down to the state of Florida and its 25 electoral college votes to decide the winner of the election. Fewer than 600 votes separated Gore and Bush, with the latter retaining a very narrow lead. This triggered subsequent rounds of time-consuming recounts and legal challenges, with both sides not giving an inch. It was only after the Supreme Court ruled in a controversial 5-4 decision (split between conservative and liberal judges) to stop the recount process that the election officially ended. The Supreme Court’s decision effectively handed Bush the White House. Al Gore conceded the race on 13 December 2000 in a graceful televised address, about 36 days after the election on 7 November 2000.

Yet, we are reminded time and again that the era of seemingly congenial politics is likely behind us. President Trump is not your conventional politician and he is certainly not Al Gore. In the absence of a strong margin of victory for Joe Biden, a Trump concession might be a very murky possibility.

It also does not help that President Trump has played up public concerns about potential fraudulent elections committed through mail-in voting, although many studies have concluded that such concerns are largely unfounded based on the data. This could whip up public frenzy and inject a lot of noise in the election process.

Ultimately, these factors serve to draw out the period of uncertainty as it relates to the election outcomes. Prolonged uncertainty may result in a more volatile market ahead.

Expect heightened volatility ahead

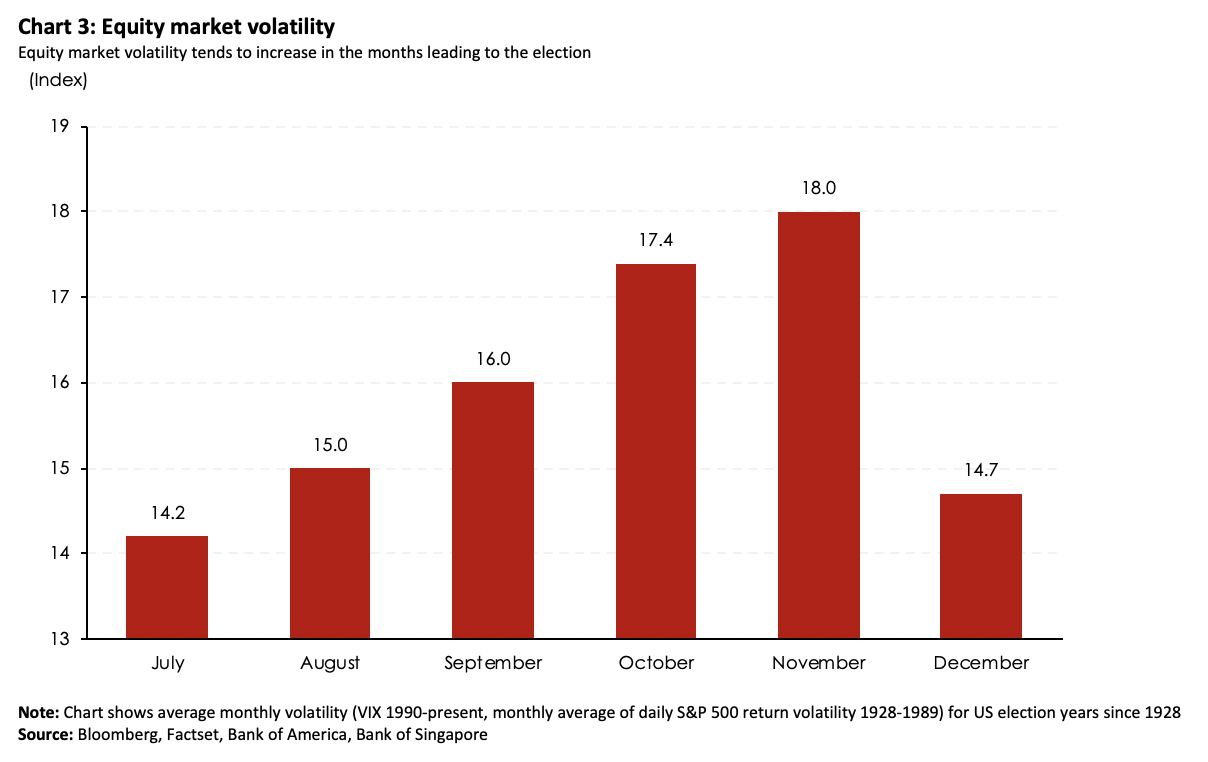

As it stands, equity market volatility is already expected to rise in the lead up to the November elections. And the data bears this out. An analysis of the S&P 500 index since 1928 show that equity volatility tends to increase 30% on average from July to November in election years.

A key reason is policy uncertainty. The market will likely react to poll numbers as they price in different scenarios that might potentially play out come election day and the possible policy ramifications to the economy and financial markets more broadly.

Add to that a potentially extended period of uncertainty about the election outcome, and you would have a potent mix for a turbulent November and December.

On the first Monday after the second Wednesday in December

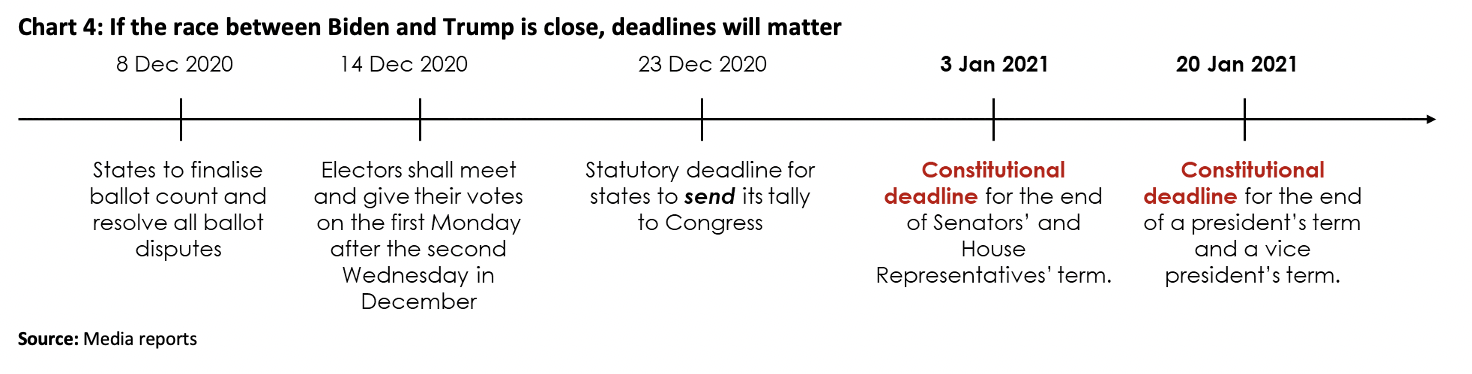

If we do reach a situation where the tabulation of the votes leads to a delay in the reporting of results (which seems inevitable) or triggers a litany of legal challenges, it pays to note that uncertainty about the election outcome will not last forever, not least because there are many statutory deadlines built into the political process. As can be gleaned from Chart 4, these deadlines are rather tight, especially when you consider the operational challenges of administering elections during a pandemic.

These deadlines can be changed in extenuating circumstances by an act of Congress. Article II of the US Constitution gives Congress the power to “determine the time of choosing the electors, and the day on which they shall give their votes, which day shall be the same throughout the United States.” Such legislation must be passed by Congress and endorsed by the President and may be subject to legal challenges in the courts. While theoretically possible, this is virtually impossible in practice. As it stands, the House of Representatives is controlled by the Democrats while the Senate and White House are controlled by the Republicans. It is a tall order for all three branches of government to approve such legislation, given the high level of partisanship in the US.

Even if Congress and the White House somehow agree to change the deadlines, there is not much flexibility in choosing alternative dates, not least because the US Constitution mandates that the new Congress must be sworn in on 3 January and that the new president’s term must begin on 20 January. These dates are clearly non-negotiable.

Consequently, despite the unprecedented nature of this election, there is a high likelihood that the deadlines spelled out in the chart below will remain this election season, much like every other election in the past. Given how tight these deadlines appear to be especially in consideration of the operational challenges involved, we can expect a great deal of noise in the political process come November, in the event of a very close race.

Is the race close?

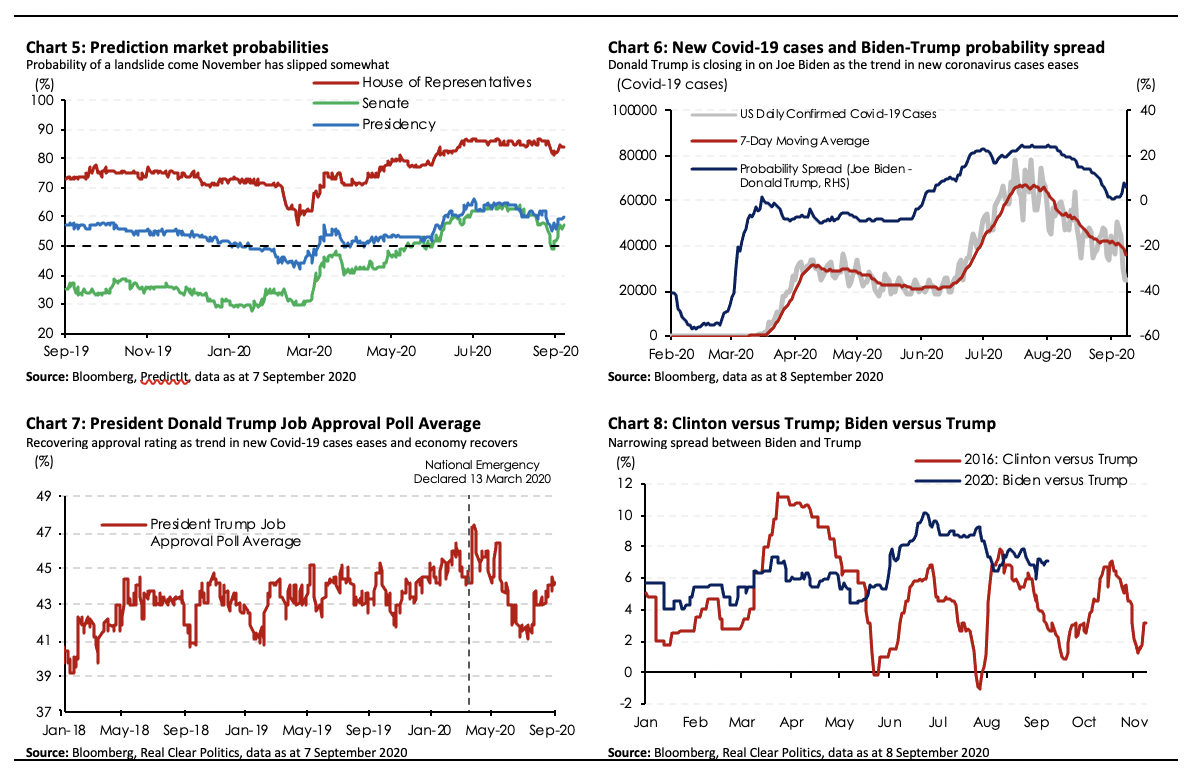

For the most part, Joe Biden has enjoyed quite a substantial lead in the polls against President Donald Trump, which to the average observer, would suggest a slam-dunk victory for Joe Biden come November. This coincided during the period when President Trump’s approval rating began falling precipitously, largely triggered by unhappiness with his administration’s early mismanagement of the Covid-19 pandemic, exemplified by a sudden surge in cases, crippling economic contraction in the second quarter and record high unemployment rate.

Yet, the situation remains fluid. We have observed a reversal of President Trump’s fortunes in the polls recently as the trend of new coronavirus cases started easing. The economy, while still mired in a deep recession, started recovering with the unemployment rate moving lower and a slew of other economic data surprising on the upside. Rapid and promising developments on the vaccine front also helped shore up his position as the vaccine-funder-in-chief. His unrelenting attacks on China have not gone unnoticed, especially among an electorate that has grown increasingly suspicious and wary of China’s position. His position as the law-and-order president became more appealing amidst violent and unruly protests, most recently in Kenosha, Wisconsin. Indeed, his approval ratings have since improved. Biden’s giant lead has steadily diminished, although he remains the odds-on favourite to win.

The recovery in President Trump’s approval rating have also coincided with diminishing odds of a Democratic sweep of Congress and the White House. In terms of the congressional races, Democrats are largely ahead of Republicans in controlling the House of Representatives. However, the probability of a Democratic majority in the Senate have seen a steady decline, with prediction markets placing 50-50 odds of the Democrats taking control of the upper chamber of Congress.

As we’ve written before, a Democratic White House and a split Congress might be good news for stock markets, as it limits the ability of Democratic lawmakers to roll back President Trump’s corporate tax cuts and also limits the passage of legislation that may introduce more onerous regulations.

On the foreign policy side of the equation, of which the White House has immense latitude to influence, a Biden administration might just mark a return to Obama-era diplomacy, characterised by alliance building and multilateralism, and less of the capricious elements that have fostered a somewhat volatile geo-political environment, including President Trump’s proclivity to govern by Tweet and rattle sabres, which are then backed by sudden unilateral actions. A less volatile geopolitical environment and a grid locked Congress might create a conducive environment for risk assets.

Still, a lot may change in the next couple of months. Impatience with an administration that seems somewhat lackadaisical in dealing with both racial injustice and bread and butter issues amid a deep recession may well boost turn out and push independent voters to the Biden camp.

As it stands, America’s electorate is becoming more diverse with Hispanics, African Americans and young Americans accounting for a large proportion of the voting set. A huge turnout of minority voters for Joe Biden may well decide the outcome.

What can investors do?

Making directional bets based on political events is often difficult. Unexpected outcomes during 2016’s Brexit referendum and the US presidential election should warn against placing too much trust in polls. The outcome of this election is highly uncertain, and we could see a close race down to the wire.

A better strategy is to position for a rise in volatility, which has consistently spiked going into such key events. This was the case in the lead up to both political surprises in 2016.

In sum, investors should be prepared for volatility in the event of an inconclusive result. In the face of a potentially extended period of uncertainty, it is reasonable to expect an increase in demand for safe havens like gold and government bonds as investors seek refuge from turbulence.

Incorporating hedges in the form of safe haven assets in portfolios might be useful to mitigate downside risks should surprises in the election process trigger a more volatile environment ahead. Portfolio diversification across asset classes, regional exposure and sectors will also matter to navigate a choppier market.

The information provided herein is intended for general circulation and/or discussion purposes only. It does not take into account the specific investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of any particular person. The information in this document is not intended to constitute research analysis or recommendation and should not be treated as such.

Without prejudice to the generality of the foregoing, please seek advice from a financial adviser regarding the suitability of any investment product taking into account your specific investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs before you make a commitment to purchase the investment product. In the event that you choose not to seek advice from a financial adviser, you should consider whether the product in question is suitable for you. This does not constitute an offer or solicitation to buy or sell or subscribe for any security or financial instrument or to enter into a transaction or to participate in any particular trading or investment strategy.

The information provided herein may contain projections or other forward looking statement regarding future events or future performance of countries, assets, markets or companies. Actual events or results may differ materially. Past performance figures are not necessarily indicative of future or likely performance. Any reference to any specific company, financial product or asset class in whatever way is used for illustrative purposes only and does not constitute a recommendation on the same. Investments are subject to investment risks, including the possible loss of the principal amount invested.

The Bank, its related companies, their respective directors and/or employees (collectively “Related Persons”) may or might have in the future interests in the investment products or the issuers mentioned herein. Such interests include effecting transactions in such investment products, and providing broking, investment banking and other financial services to such issuers. The Bank and its Related Persons may also be related to, and receive fees from, providers of such investment products.

No representation or warranty whatsoever (including without limitation any representation or warranty as to accuracy, usefulness, adequacy, timeliness or completeness) in respect of any information (including without limitation any statement, figures, opinion, view or estimate) provided herein is given by OCBC Bank and it should not be relied upon as such. OCBC Bank does not undertake an obligation to update the information or to correct any inaccuracy that may become apparent at a later time. All information presented is subject to change without notice. OCBC Bank shall not be responsible or liable for any loss or damage whatsoever arising directly or indirectly howsoever in connection with or as a result of any person acting on any information provided herein.

The contents hereof may not be reproduced or disseminated in whole or in part without OCBC Bank's written consent. The contents are a summary of the investment ideas and recommendations set out in Bank of Singapore and OCBC Bank reports. Please refer to the respective research report for the interest that the entity might have in the investment products and/or issuers of the securities.

This advertisement has not been reviewed by the Monetary Authority of Singapore.

Cross-Border Marketing Disclaimers

Please click here for OCBC Bank's cross border marketing disclaimers relevant for your country of residence.