Big bad Biden?

The Biden agenda

As investors are well aware, markets hate uncertainty. In this election cycle, the prospect of a Joe Biden victory alongside a Democratic sweep of both the House of Representatives and the Senate represents the more uncertain outcome, not least because it portends big policy changes ahead.

Should a blue wave come to pass, a key question would be: Is the Biden agenda conducive for risk assets? More importantly, can a Biden administration realistically enact the policies he has set forth during his campaign?

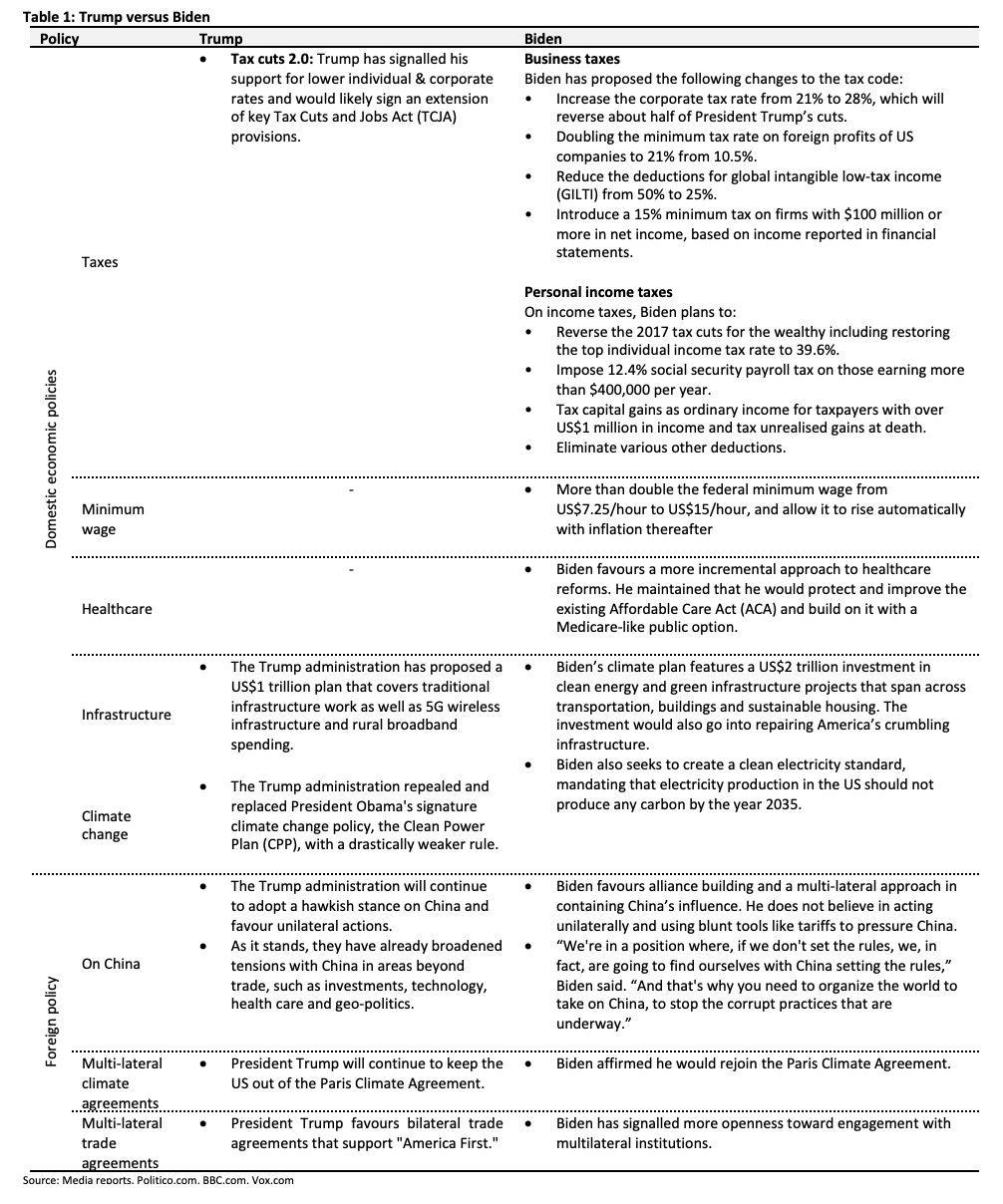

Table 1 provides an overview of the types of policies the Biden campaign has proposed in this election cycle, in stark contrast against what little the Trump administration has put forth in terms of actual, concrete proposals. Three key areas would be of particular interest to markets. They are:

- Taxes and spending

- Regulation

- Trade

Taxes – a tale of contrasts

While the Trump administration’s foreign and trade policies have been problematic for markets, their market-friendly domestic economic policies have been a boon for risk assets, particularly their stance on deregulation and corporate tax cuts. A cornerstone achievement of the Trump administration is the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) in late 2017, which among other things, cut the effective corporate tax rate from 35% to 21% and lowered the personal income tax rates for most of the income brackets. These tax provisions are temporary and will expire after 2025. Should they win a second term, the Trump administration would look to make permanent some of the temporary tax provisions from the 2017 package and would also look at pushing for another round of tax cuts.

By contrast, Joe Biden is looking to move taxes in the opposite direction. On the business front, Mr Biden has proposed the following changes to the tax code:

- Increase the corporate tax rate from 21% to 28%, which will reverse about half of President Trump’s cuts.

- Doubling the minimum tax rate on foreign profits of US companies to 21% from 10.5%.

- Reduce the deductions for global intangible low-tax income (GILTI) from 50% to 25%.

- Introduce a 15% minimum tax on firms with $100 million or more in net income, based on income reported in financial statements.

On income taxes, Mr Biden plans to:

- Reverse the 2017 tax cuts for the wealthy including restoring the top individual income tax rate to 39.6%

- Impose 12.4% social security payroll tax on those earning more than US$400,000 per year

- Tax capital gains as ordinary income for taxpayers with over US$1 million in income and tax unrealised gains at death.

- Eliminate various other deductions.

Bad for earnings

From the outset, Mr Biden’s tax agenda is not market friendly. It will have a direct negative impact on company earnings and therefore impact stock markets. After all, the Trump tax cuts drove the re-rating of stocks and pushed stock markets sustainably higher over the course of President Trump’s first two years in office.

On earnings, according to the Bank of Singapore, the higher corporate tax rate alone will reduce S&P 500 company earnings by 5% - 6%. The higher GILTI tax and 15% minimum tax will hit earnings by another 5% - 6% and 0% - 1%, respectively. All in, Bank of Singapore estimates Biden’s tax proposals will reduce S&P 500 earnings by 12% - 13%. In this regard, Mr Biden’s tax agenda is by no means market friendly.

Apart from the corporate tax code, an increase in the tax rate applied to capital gains and dividends for the highest income individuals may have an impact on markets as well. If history is a guide, households typically decrease equity allocations ahead of capital gains tax rate hikes. Event studies show that such tax hikes are often associated with a short-term decline in equity prices as well as an underperformance of high momentum stocks that typically deliver the highest taxable gains to investors ahead of the tax hike. However, higher tax rates seldom dim the appeal of equities over the long-run and investors tend to re-establish any equity positions they sold ahead of the tax change after some lag. Household equity allocations increased in the 6 months after each of the 3 capital gains tax rate hikes over the past 40 years.

Build back better

The economic impact of Biden’s tax plans is more ambiguous. An analysis by the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB) found that Biden’s tax plans would raise between US$3.35 trillion and US$3.67 trillion over ten years if enacted in full starting in 2021, which amounts to about 1.3% to 1.4% of GDP. The Tax Policy Centre estimates that Biden’s policies will bring in about US$4 trillion of revenue over the next decade.

On its own, an increase in taxes represents a major fiscal contraction, which could slow down the pace of economic growth and shrink labour supply by discouraging work and capital accumulation. But this is unlikely to spell doom for the economy.

First, the proposed changes to the personal income tax codes shift the tax burden towards wealthy Americans, who are most able to afford it. While it might hurt sectors exposed to high-income spending like luxury retail, residential real estate and transport, it is unclear if this has a straightforward negative impact on the economy as the marginal propensity to consume for high-income segments is typically small as compared to the middle and lower income segments. The high-income cohort has a fairly high propensity to save additional income, and taxes on their income may mark a loss of material flow into financial markets, as opposed to a permanent loss in aggregate spending, which matters more to the economy.

Second, the revenues raised from higher taxes will likely be used to finance a substantial increase in Federal spending. The Biden campaign has proposed a slew of ambitious spending commitments including investments in clean energy, repairs to America’s crumbling infrastructure and a number of other green infrastructure projects in areas such as transportation, buildings and sustainable housing. The clean energy and infrastructure spending package alone is expected to cost more than US$2 trillion over four years. An additional US$700 billion will be set aside over four years for a “Made in America” plan which includes government funding for the procurement of goods and services that are produced domestically and funding for research and development for clean energy.

Furthermore, plans to improve and expand the Affordable Care Act by incorporating a Medicare-styled public option as well as increasing spending on public education and affordable housing rounds out a comprehensively expansionary fiscal agenda.

Indeed, it is an opportune time for the Biden administration to push for bold ideas and expansive public spending initiatives, given that they may take the reins of government during a period of high cyclical and structural unemployment and deep economic contraction. Fiscal deficit hawkery may take a back seat under such dire economic conditions. After all, even Fed officials are endorsing more – not less – fiscal spending.

In this regard, a comprehensive infrastructure spending bill would check multiple boxes, including boosting employment, expanding the use of green technologies (thereby making inroads in the climate change agenda) and improving existing public infrastructure, public transport and communication systems. Such extensive public investments would be a boon for both the economy and financial markets.

The Penn Wharton Budget Model values Biden’s spending proposal at US$5.4 trillion over the next 10 years, eclipsing their estimates of US$3.4 trillion raised from higher taxes across the same period of time. Overall, Biden’s spending proposal and tax plans represents a net expansionary fiscal agenda. This should be reflationary in nature, which is typically supportive of commodities and risk assets.

From deregulation to more regulation?

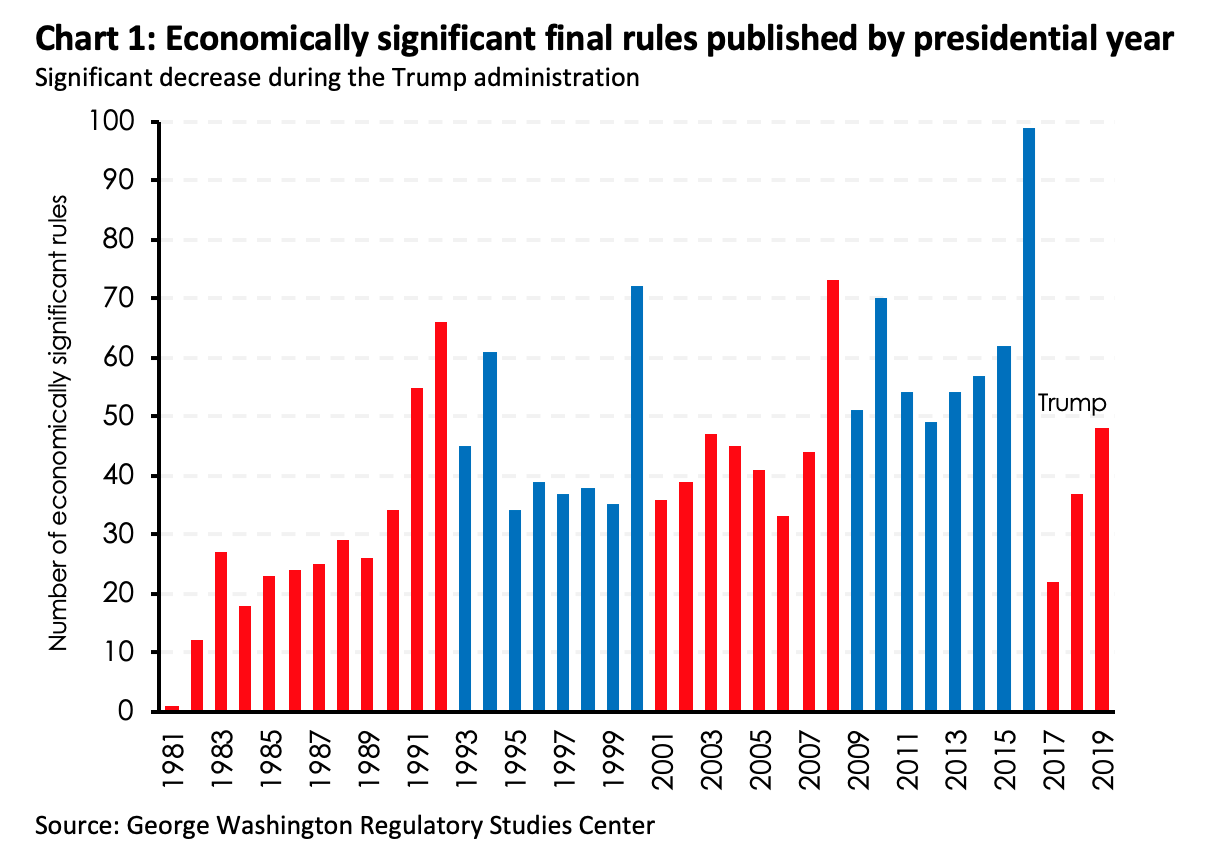

Aside from tax cuts, President Trump has made deregulation a key tenet of his economic agenda and has rolled back many Obama-era rules and regulations. He has been successful for the most part, issuing the least number of economically significant rules and regulations compared to past administrations.

Deregulation and tax cuts were among the key drivers for Wall Street’s ascent during the first two years of his administration, before the market hit multiple air pockets in the form of the trade war, the slump in manufacturing and rising interest rates. Of course, the biggest air pocket of all is the current Covid-19 pandemic.

Should President Trump win the election, deregulation will remain a key plank of his economic agenda. Wall Street can depend on policy continuity on the regulatory front. The Trump-induced deregulation trend will face disruption from a Biden administration.

Joe Biden can influence the regulatory landscape in two ways. The first is through the nominations he puts forth for chief positions in the various regulatory agencies, including the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the Environmental Protection Agency, the Securities and Exchange Commission and others. He could nominate career regulators to fill these leadership positions, specifically those who might favour tighter supervisory standards and seek to actively use the authority given to them to regulate key economic sectors, including finance and the environment.

At the same time, Biden can also allocate more funding to these agencies to provide more resources to perform their regulatory functions. Indeed, one way the Trump administration has weakened the regulatory environment is through actively defanging these regulatory agencies by nominating individuals with very little regulatory experience and who favour a light-touch approach to regulation as well as cutting funding.

Second, the Biden administration may seek to reinstate regulations that the Trump administration has scaled back and may seek to pass fresh legislations on thorny issues like drug pricing and climate change. For instance, Biden’s climate change agenda includes eliminating fossil fuel subsidies, banning new drilling on federal lands and waters, imposing various environmental restrictions and reinstating existing regulations that were weakened under the Trump administration, such as coal and car emission standards. Pharmaceuticals, health insurers and energy companies may potentially be in the firing line from Biden’s regulatory agenda.

Meanwhile, banks and tech companies could come under heavy scrutiny from a Democrat-led Congress and a Biden administration, especially as it pertains to anti-trust actions. Already, the Democrat-led House of Representatives has proposed a series of far-reaching antitrust reforms to curb the market power of big tech companies, contained within a 449-page report. This represents the most dramatic proposal to overhaul competition law in decades and could lead to the breakup of tech companies if approved by Congress. It may not be implemented in its current form, but its publication already signals intent.

On the labour market front, the Biden campaign seeks to strengthen the bargaining power of workers by making it easier for workers to unionise. The most significant of his plans is the proposed doubling of the Federal minimum wage from the current US$7.25/hour to US$15/hour. While raising the minimum wage might increase the cost for firms, it also puts more money in the hands of workers who have a higher marginal propensity to consume and would therefore increase aggregate demand.

President Trump’s deregulation efforts have not translated into any meaningful boost to growth, although we cannot discount that there might be some beneficial long-term impact to productive capacity that is currently unobservable. Likewise, a rollback of his deregulatory agenda need not mean disaster for the US economy. Indeed, empirical evidence that increased regulation results in weaker economic growth is mixed at best. Also, in the face of a climate catastrophe, significant strengthening of environmental regulations is almost inevitable and is a global trend. In addition, we should not be surprised that heightened concerns about anti-competitive behaviour and data privacy issues in the tech sector will almost surely invite greater regulatory scrutiny. It might not be the economy that takes the hit on aggregate, but it may well be the stocks of companies operating in the sectors most impacted by these regulatory changes such as health care and energy that will face pressure.

Trade – More multilateralism; Less unilateralism

After almost four years of unpredictable foreign policy, a reversion towards more conventional, predictable and less disruptive type of policy making might be welcome by the markets. In this regard, a Biden administration would be an unambiguous plus point for the markets.

Indeed, a Biden administration would mark a reversal to Obama-like strategic diplomacy and multilateralism and eliminate the capricious elements that tended to characterise President Trump’s approach to foreign policy.

This does not mean that a Biden administration would necessarily mark a reversal of US-China relations. Tensions between the US and China will remain as containment of China’s geo-political and global economic ambitions share strong bipartisan support. But the manner of engagement will likely be less unpredictable. While the Biden administration may not ease tariff barriers immediately, they are unlikely add to them, given Biden’s stern opposition against unilateral action and using tariffs as bargaining chips. Instead a Biden administration would likely favour alliance building and adopt a strategic multi-lateral approach to pressure China.

Biden has also shown a willingness to compartmentalise foreign policy issues, favouring cooperation on issues of global concern such as climate change and the pandemic, while challenging China on other fronts such as human rights abuses, corporate espionage, flouting of international trading agreements and geo-political aggression. The non-conflation of issues ensures that the administration’s foreign policy response would be more predictable, as opposed to the sorts of “cliff-hanger”, “tune in for more” type policy reprisals under the Trump administration.

To be clear, a Biden presidency does not necessarily mean a return to unfettered globalisation or that the US and China will hold hands and sing kumbaya. Tensions will remain, but chaotic policy responses may recede. The decoupling of the US and China economies will likely persist as a long-term trend, but the foreign policy environment might be less uncertain. This is a clear positive for businesses.

What you hear and read is rarely what you get

A Democratic sweep of the executive (White House) and legislative branches of government (House of Representatives and Senate) gives the President immense latitude to implement his policy agenda. Historically, a government unified under one political party has been able to deliver dramatic policy changes – think Obamacare in 2009 and the Trump tax cuts in 2017. Should Biden preside over a Democratic landslide, he would be in a strong position to push through tax increases, higher minimum wage and an ambitious green infrastructure and clean energy spending plan.

That does not mean his policy ambitions are greenlit by Congress willy-nilly without challenges and moderation. Ultimately, Congress is a buffer between a president’s policy aspirations and the real economy. Campaign promises are rarely implemented in their original form. Policy proposals are typically watered down and moderated as Congress requires a majority to pass the legislation, and as long as the political centre holds, the provisions in the resulting bill would have moved closer to the centre from left-leaning extremes to build a “consensus” agreement.

The size of the majority in the Senate matters

Typically, the Senate holds the key to passing major legislation. Even if the Democrats gain control of the Senate, it does not mean they will necessarily have the votes to pass major spending bills easily on partisan lines. This is because the party in the minority position can always make use of the filibuster to debate a piece of legislation endlessly, hence delaying or preventing a vote on a bill. 60 votes in the Senate is required to end the filibuster or cut off debate on most measures and force a final vote on a piece of legislation.

In an ideal, non-partisan world, Democrats and Republicans should be able to negotiate and compromise on a final bill that receives ample bipartisan support, such that it organically ends the filibuster. Alas, this is political fantasy in the modern era. Voting along partisan lines will likely remain a fixture of the current political climate.

As such, if Democrats win just a slim majority in the Senate, they will not be able to block the filibuster unilaterally and will have to work across partisan lines to push through meaningful policy changes. If they win a supermajority (i.e. more than 60 seats), they would be in a strong position to deliver sweeping policy changes. Yet, the chances of the latter happening is very slim. The last time Democrats enjoyed such a big majority was way back in the late 1970s (1975 to 1979). The Democrats came very close during the Obama-led blue wave election in 2008 which resulted in 57 Democratic seats in the Senate, with two independent seats that caucused with the Democrats, just 1 seat shy of a supermajority.

There are other ways to fast track legislation through the Senate without a filibuster-proof majority. One of the ways is the reconciliation process, which allows bills to be passed with a simple majority in the Senate. However, there are many limitations built into this process to curtail its use. For instance, it is only applicable for budgetary bills, or bills that are primarily fiscal in nature, such as changes to the tax codes or public spending. It is also limited to one spending or revenue bill per year and the bill cannot increase deficits outside the 10-year budget window. Working within these confines and adjusting the bill to win over the support of centrist or moderate Senators (i.e. the marginal voter or the 51st vote) would necessarily result in a scaled down or less ambitious spending plan.

In addition, without a filibuster-proof majority, many policy changes would inevitably require bipartisan support, especially in the areas of regulation, which is not covered under the reconciliation process. Minimum wage, anti-trust legislation, financial regulatory reforms and energy and environmental regulatory proposals would fall in this category, requiring the endorsement of at least 60 Senators to pass. Consequently, legislation on these fronts will likely be softened to garner bipartisan support. Admittedly, this itself is an optimistic thought amid a deeply partisan climate.

Indeed, if backed to a corner by an uncooperative and obstreperous Republican party bent on blocking major legislation, a Democrat-majority in the Senate could simply trigger the “nuclear option” to override an existing procedural rule with a simple majority. Essentially, with 51 votes, Democratic Senators can eliminate the filibuster procedure entirely, such that they would be able to pass any major policy changes and legislations with a simple majority in the Senate. This already has a precedent. The “nuclear option” was triggered by a Democrat-led Senate in 2013 to push through executive branch nominations and judicial appointments. It was later used again in 2017 when a Republican-led Senate sought to push through a Supreme Court nomination.

This is a controversial move as it could lead to erratic changes in policies in future election cycles. Others would argue that the filibuster has been abused to block important legislative action in recent years, hence eroding the usefulness, credibility and trustworthiness of Congress and should be removed if the Democrats gain a sizeable majority in the Senate. Even an institutionalist like former President Barrack Obama has endorsed this idea. For his part, Joe Biden seems sympathetic to this view as well, telling reporters in July that “depend(ing) on how obstreperous [Republicans] become … I think you’re going to just have to take a look” at abolishing the filibuster.

A divided Congress? Forget about massive policy changes.

If Congress remains divided – Democrats retain control of the House of Representatives and Republicans retain the Senate – it will be an uphill task to deliver any major policy changes, especially in the current partisan environment. Legislations will likely have to be watered down far more than before in order to achieve bipartisan agreement in the Senate. And this is if Senate Republicans are willing to play ball – a big if. A Republican-led Senate could simply refuse to debate any Democratic policy motions.

In this case, the Biden administration will likely have to focus on a few key issues that share broad bipartisan consensus. This may include prioritising infrastructure spending, drug pricing and oversight on US tech. Legislation to increase taxes for corporations and wealthy individuals might be dead on arrival at the Senate.

Stimulus support for Covid-19 times almost guaranteed

Right out of the gate, a Biden administration would highly likely seek to pass a fresh stimulus bill to aid the current economic recovery. The market seems positive about this, having rallied over the past week on expectations that the successful passage of an expansionary fiscal plan would almost be a given no matter who the occupant of the White House is. This is despite concerns that a blue wave come November could augur higher taxes.

There are a number of rational stories one could speculate to explain the market’s seemingly unbridled optimism despite the spectre of higher taxes from a Biden administration. First, on aggregate, the net effect of Biden’s fiscal agenda is expansionary as tax increases will be used to fund a significant increase in federal spending. What’s good for the economy must be good for the markets. Second, the Biden administration might deprioritise tax increases in light of the stalling economic recovery and high unemployment rate and might delay tax increases until after the economy is on more stable ground. Third, even with a majority in Congress, changing the tax code is a complicated affair and would not be passed through immediately, given other legislative priorities. This would buy the market some time.

So, is Joe Biden bad for the markets?

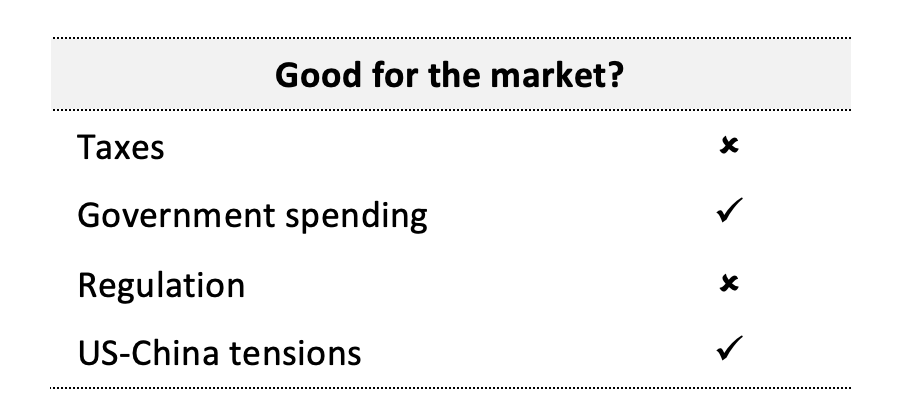

In sum, from the perspective of the market, we could summarise our view in the following table:

On net, perhaps a Biden administration is good for the markets. However, we also note that what we see in campaign promises is seldom what we get. Whether or not a Biden administration gets to push through their reformist agenda and ambitious and far-reaching tax and spending plans will depend on the shape and contours of Congress. A Biden administration generally points in the direction of higher taxes and even higher spending, tighter regulation and more conventional approach to foreign policy. While the direction might be clear, the final outcome isn’t.

In any case, we could observe three potential outcomes in November:

- A Democratic sweep. A Democratic sweep of the White House and Congress might not be all that bad for the market, even if it increases the likelihood of higher corporate and capital gains taxes and tighter regulation. Biden’s plans to significantly ramp up government spending and investments on infrastructure, healthcare and clean energy would inevitably lead to a net expansion of the fiscal deficit and might be reflationary for the US economy. This is a positive for risk assets and commodities over the long term. Biden’s more predictable and less capricious approach to trade and foreign policy will also reduce geo-political uncertainty, which is another positive for the markets as well. Yet, concerns about higher taxes and tighter regulation will continue to hang over markets.

- Biden wins, but Congress stays divided. A Biden win with a Republican Senate and Democratic House might be beneficial for markets over the long run, as we will likely see a more strategic and less capricious approach towards China from the White House while a divided Congress means Trump’s tax cuts are unlikely to be rolled back and fresh regulations might be blocked in the Senate.

- Status quo: Trump wins and Congress remains divided. A Trump win could increase the likelihood of further deregulatory efforts and tax cuts, although these would be difficult to pass through in a divided Congress. Policy continuity would also come at the expense of a more unpredictable US-China strategy.

The information provided herein is intended for general circulation and/or discussion purposes only. It does not take into account the specific investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of any particular person.

Please seek advice from a financial adviser regarding the suitability of any investment product taking into account your specific investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs before you make a commitment to purchase any investment product.

The information in this document is not intended to constitute research analysis or recommendation and should not be treated as such. This does not constitute an offer or solicitation to buy or sell or subscribe for any security or financial instrument or to enter into a transaction or to participate in any particular trading or investment strategy.

Any opinions or views of third parties expressed in this material are those of the third parties identified, and not those of OCBC Group.

No representation or warranty whatsoever (including without limitation any representation or warranty as to accuracy, usefulness, adequacy, timeliness or completeness) in respect of any information (including without limitation any statement, figures, opinion, view or estimate) provided herein is given by OCBC Bank and it should not be relied upon as such. OCBC Bank does not undertake an obligation to update the information or to correct any inaccuracy that may become apparent at a later time. All information presented is subject to change without notice. OCBC Bank shall not be responsible or liable for any loss or damage whatsoever arising directly or indirectly howsoever in connection with or as a result of any person acting on any information provided herein.

OCBC Bank, its related companies, their respective directors and/or employees (collectively “Related Persons”) may or might have in the future interests in the investment products or the issuers mentioned herein. Such interests include effecting transactions in such investment products, and providing broking, investment banking and other financial services to such issuers. OCBC Bank and its Related Persons may also be related to, and receive fees from, providers of such investment products.

The information provided herein may contain projections or other forward-looking statement regarding future events or future performance of countries, assets, markets or companies. Actual events or results may differ materially. Past performance figures are not necessarily indicative of future or likely performance. Any reference to any specific company, financial product or asset class in whatever way is used for illustrative purposes only and does not constitute a recommendation on the same.

Investors should note that there are necessarily limitations and difficulties in using any graph, chart, formula or other device to determine whether or not, or if so, when to, make an investment.

The contents hereof are considered proprietary information and may not be reproduced or disseminated in whole or in part without OCBC Bank’s written consent.

Cross-Border Marketing Disclaimers

Please click here for OCBC Bank's cross border marketing disclaimers relevant for your country of residence.